Cover Image courtesy of Geva Mentor

In an Australian first, Suncorp Super Netball players will now have access to wide-ranging reproductive health care.

The groundbreaking deal – potentially unique worldwide – will include education around menstrual cycles and their intersection with physical and reproductive health, and access to free fertility assessment.

Having access to this gender-specific education is important for a wide range of reasons.

An athlete’s peak years of fertility and peak performance almost completely overlap, while there’s limited research on health disorders relating to female athletes. They also carry a higher-than-normal risk of menstrual dysfunction that can impact physical health, performance, fertility and even injury risks.

Players had been sharing their concerns colloquially, but the Australian Netball Players Association (ANPA) inaugural Wellbeing Survey earlier this year revealed just how much of a hot topic women’s health care has become.

Former Diamond captain and longtime CEO of ANPA, Kathryn Harby-Williams AM said, “Over 50% of athletes surveyed said they had concerns about fertility and 90% said that they would be interested in having a fertility health check. Those figures are astounding and showed us this was an area that we really needed to address.”

ANPA will work in conjunction with IVF Australia, Melbourne IVF, Tas IVF and the Queensland Fertility Group to put the initiative into place, making it one of the final puzzle pieces in providing relevant, holistic care in netball.

Melbourne Maverick and former Australian Diamond Tara Hinchliffe said, “I think this partnership is a huge step in recognising that females are different to males, and in sport we have different needs sometimes.

“Menstrual health and fertility are topics we talk about at training nearly every day. So having that education and being able to make informed decisions about whatever it might tell us, is going to be really important for us all.”

Dr Kath Whitton, a fertility specialist with IVF Australia, said having access to greater knowledge and screening tools will empower athletes. “As part of the programme we will be providing professional netball players with access to fertility testing and to specialists to discuss their personal situation, interpret their results and come up with personalised plan for themselves.

“We aren’t trying to fearmonger players or make them anxious, but give them clarity and confidence. It’s purely about making proactive and informed decisions regarding their own wellbeing and future.”

Nat Medhurst (now Butler) played 86 games for the Australian Diamonds, winning three world titles along the way. Having struggled with fertility and multiple miscarriages, she’s been a strong advocate for the support now on offer.

“In my 17 years as an athlete we went through so many tests from a performance perspective, but never once was my health as a female ever questioned. Netball is a very rigorous sport, and it wasn’t until I left the sport and wanted to start a family that I realised it wasn’t going to be as easy as I thought it would be.

“So for players to have access to specialists, to feel safe to ask questions about starting a family, their fertility, freezing eggs or whatever they might need, is so important to be able to make informed decisions about their health.”

While fertility could be seen as more relevant to maturer athletes, having information and screening available is vital to all ages, as it can help inform their current and future health care. Hinchliffe said that interestingly younger athletes have been the most hungry for it.

“When you’re starting out as an athlete you don’t always know who to talk to or where to get your information from. So our younger players are often the ones starting these conversations. They will come to those of us who’ve been around for a while and ask, ‘Is this normal?’

“Knowledge is power and having this information empowers and gives us confidence to make decisions about our health care and what we need to be aware of.

“When it comes to fertility, one of our fears when we first start playing is getting pregnant, and then as we get older it becomes around not being able to get pregnant, and you don’t learn about that at school.

“The message from us older players is to make the most of these opportunities because we could have done with them years ago when I first came into the league.”

With female athletes more visible than ever and seen by many as role models, sport can be a powerful platform to inform the wider public. Hinchliffe hopes discussion about women’s health will help others to be more comfortable chatting about topics that may previously have been seen as embarrassing or taboo.

“Being able to start these conversations about fertility and menstrual health is really important, and it leads into topics such as well being and the overall big picture of what we are as women and some of the unique issues we have to deal with.

“For girls and boys to find out information and knowledge as soon as they can, to be able to talk to others and make informed decisions. It all helps them feel more confident and healthier while they’re growing up.”

With the programme newly underway, education sessions have started, and athletes are already starting to access fertility testing, according to Harby-Williams. She said measuring its success will be easy.

“It’s helping even one athlete address some issues that they’ve uncovered. Success also looks like giving athletes peace of mind by taking away another stress when they already carry so much pressure on their shoulders.”

Captain Kath Harby-Williams (second from left) and the Australians celebrate gold at the 2002 Commonwealth Games. Image: Leon Mead

—

Who will the care be available to?

The education and access to fertility testing will be available to all female athletes within Suncorp Super Netball, including its many imports.

ANPA will also work with staff from the eight SSN clubs to give them greater clarity around the programme and what it could entail. Harby-Williams said, “We are in the process of updating our pregnancy and parental policy, and this is obviously a component of that.

“If players do need fertility treatment they will most likely do that in their downtime. But if they need some support, then we will work with their Wellbeing leads and their teams to help them navigate that.”

—

What is available under the partnership?

Initially, athletes will have access to workshops, webinars, podcasts and online education which will make fertility knowledge accessible to all.

If an athlete does have an area of concern about their menstrual cycle and the many factors which could impact their future reproduction, their next step is to talk to one of the fertility experts aligned with the programme. This can be done in person or via a telehealth consult, where the specialist gains a thorough understanding of the athlete’s current physical health and any problems they might be facing.

From that point an athlete can access a fertility assessment that includes a pelvic ultrasound and an AMH (Anti-Müllerian Hormone) blood test.

If areas of concern are detected, the fertility specialist, athlete and any other parties they wish to include can put an individualised assessment and treatment plan in place. ANPA will support athletes by providing contacts for any further and necessary health care.

A long term advocate for holistic health care for female athletes, reproductive literacy is one of Medhurst’s passions, leading her to share some of her personal experiences in the push for better education for women.

“I’ve always found it easy to speak out,” said Medhurst, “but I think that sometimes it can give you a reputation as a troublemaker. But that’s never been my intention.

“As women we are conditioned not to talk publicly about our menstrual cycles. And I’m a firm believer that information can make us better educated to make decisions that work for us. To learn what is normal and what isn’t, what can be some of the underlying issues. Women shouldn’t have to fight to get answers about their bodies, and this initiative will hopefully give women more control around their bodies and their health.

“Education is such a vital piece that’s been missing for a long time.”

Harby-Williams agrees. She said, “My era didn’t discuss it at all. I had irregular and painful periods, but not for one moment did I think it was necessary to discuss it. Like many others I just thought it was part of being a young woman and dealt with it myself. I didn’t know it was abnormal, and looking back now I was incredibly lucky to have children after I retired.

“So I love the fact that our players are using their platforms and voice to try and normalise a lot of complex conversations, including this one.”

Nat Medhurst is a long time advocate of gender specific education for female athletes. Image: Aliesha Vicars

—

How are pelvic ultrasounds and AMH blood tests used in assessing fertility?

A pelvic ultrasound looks at the uterus, ovaries, cervix, vagina, bladder and fallopian tubes to help identify conditions such as fibroids, cysts, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis and blockages that can interfere with fertility. A specialised antral follicle count can be used to count the follicles and estimate ovarian reserve. It’s a minimally invasive test.

The AMH blood test measures the level of Anti-Mullerian hormone, which is an indicator of the number of eggs left, and how that compares for a woman’s age. It can be done at any point during the menstrual cycle, and can be used across time to see how quickly AMH levels are declining.

Women are born with millions of eggs, but supply and quality constantly drops across their life span. By puberty, just several hundred thousand remain and this number continues to drop rapidly. Testing for egg numbers is an important tool in assessing fertility, according to Dr Whitton.

“If a woman has a low egg count for her age, it doesn’t tell us about her chances of pregnancy, but it does tell us that she may run out of eggs earlier than another woman her age or go through menopause a little earlier than the average age.

“So in terms of fertility, she may have fewer years available to her for childbearing because she may run out of eggs earlier.

“When thinking about healthy versus areas of concern for athletes, my key message for them is to track their menstrual cycles and use them like a vital sign.

“They’re used to tracking things like their sleep or nutrition, so they can similarly track menstrual cycles which reveal a lot about their overall health.

“And when they can see abnormalities such as irregular cycles, heavy bleeding or pain, that is an indication to seek further assistance because it may be something that needs attention.”

—

Why is fertility such a concern for female athletes?

Elite female athletes can experience far greater risks of menstrual dysfunction, including amenorrhea (absence of menstrual periods), oligomenorrhea (irregular menstrual periods), luteal phase defect (lack of progesterone for a healthy uterine lining), and anovulatory cycles (absence of ovulation). The proportion of elite athletes who experience such irregularities can shockingly be as high as 65% in distance runners, compared to up to 11% in the wider population.

Causes of dysfunction can include specific conditions such as Relative Energy Deficiency Syndrome (REDs), functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA), polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and endometriosis, intense physical exertion, and the challenges of training and competition schedules among many other factors.

REDs is a condition caused by energy expenditure that is greater than energy intake, and it can have profound impacts on an athlete’s performance and energy levels, reducing muscle strength, and impacting bone, cardiovascular, metabolic, menstrual and reproductive health. While the intersection between fuelling the body and training is now carefully managed, some athletes, particularly during heavy training or competition phases, are still prone to being impacted.

One of the primary causes of functional hypothalamic amenorrhea, REDs impacts fertility by altering the body’s hormonal balance, leading to changes in ovarian function and oestrogen deficiency.

Polycystic ovary syndrome is a condition that impacts between 20 and 40% of elite female athletes, compared to around 10% of the regular population. It is characterised by higher bone and muscle mass which can improve performance, and is potentially why so many women with PCOS go on to excel at sport. However, it also causes a range of menstrual irregularities which may need treatment especially if they impact on fertility.

Dr Whitton explained, “At one point or another in an athlete’s life, many of them will experience REDs. It’s really important to identify REDs and polycystic ovary syndrome early on, and monitor and treat them because they can have significant and long term health implications. Adequate refueling alone may be enough to re-establish a menstrual cycle, and that’s so important for overall health and adequate performance, as well as for future reproductive health.

Endometriosis is a condition where excess tissue grows in the pelvic area, and impacts 10% of all women. It can take up to seven to 10 years for diagnosis, and may have a profound effect on elite athletes. Severe pain, heavy bleeding and physical and emotional fatigue are just a few of the symptoms that can be detrimental to their careers. Education, assessment and treatment of symptoms are powerful tools in its management, helping athletes to continue their careers.

Tayla Williams (Adelaide Thunderbirds) struggles with endometriosis have impacted her netball career. Image Tahliah Harding.

There are also other factors which can increase fertility issues in female athletes.

In an era of increasing professionalism, female athletes are staying in elite sport for longer. For team sports, that is on average a further six years. However, as women age, they experience an exponential decrease in their ovarian reserve and quality of their eggs, making a successful pregnancy more challenging.

Training load is another facet of sport that can impact reproductive health, and while moderate amounts of physical activity are healthy, it’s been shown that the intense physical regimes of elite athletes can cause an increase in fertility issues between two and six fold depending on the sport they compete in.

Contraceptive use can be essential to manage an athlete’s menstrual cycle. For women who experience heavy, painful and/or irregular periods, the use of oral contraceptives or intrauterine devices (IUD) can reduce their symptoms during crucial times of training and competition. However, they can also cover a range of issues during use and make exploring reproductive health more challenging.

Dr Whitton said that assessment can still occur. “We’ll talk about what their periods were like prior to using any contraception, and any other symptoms that may surround their cycles, as they will often still get cyclical symptoms.

“You don’t need a Mirena (IUD) taken out for the blood test, although the pill would have to be stopped to get an accurate measurement of AMH.”

There’s also increasing evidence that contraception may be of benefit in regulating hormones and therefore reducing injury risks. In the first half of the menstrual cycle oestrogen climbs and peaks just before ovulation, potentially causing some ligamentous laxity. Some recent studies have suggested that injuries such as anterior cruciate ligament ruptures may be more common at this stage of the menstrual cycle.

Hinchliffe, who has twice experienced the devastation of an ACL rupture, is excited that up to date information about athlete’s menstrual cycles might help with injury prevention strategies. “At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter where you’re at in your cycle, it’s your job and you have to turn up.” she said.

“So having that knowledge and an understanding of where your body might be at in its cycle allows you to talk to medical and strength and conditioning staff about what that means. It gives us greater confidence to play.”

Dr Whitton added, “While the research is ‘watch this space’ at the moment, the developments are exciting. It’s allowing us to individualise advice and training approaches around cycles, although that is harder in a team sport setting.”

While the new partnership won’t produce any official research into athlete’s reproductive systems, Dr Whitton hopes that just as they will be become better informed, so will fertility experts. “This area is a big personal interest of mine. So while nothing is approved, this work will help our understanding of the issues that athletes face and improved approaches to managing them.”

Tara Hinchliffe (far right) has experienced two anterior cruciate ligament ruptures during her career. Photo: Simon Leonard

—

What happens if there is a concern with an athlete’s fertility

For some athletes, the number and/or quality of their eggs may require help to preserve future fertility. For others, age is a crucial factor in their decision making.

In days gone by, athletes often had to retire if they wanted to start a family. With increasing professionalism, monetisation and goals they may wish to achieve, women are staying in team sports for longer. That can seriously impact their chances of having a healthy pregnancy.

Dr Whitton said, “As we get older, eggs make more mistakes when they’re developing. And so if fertilisation occurs, you can see things like chromosomal abnormalities in embryos going up, because it all comes back to ovarian ageing.”

Preserving eggs via harvesting and freezing (oocyte cryopreservation) is a process that more athletes are electing to do, with age critical in achieving a successful pregnancy later on. Research has shown that if eggs are cryopreserved when the donor is under the age of 35, around 52% of women are later able to progress to a live birth. That number drops dramatically to just 28% if eggs are retrieved after the age of 35.

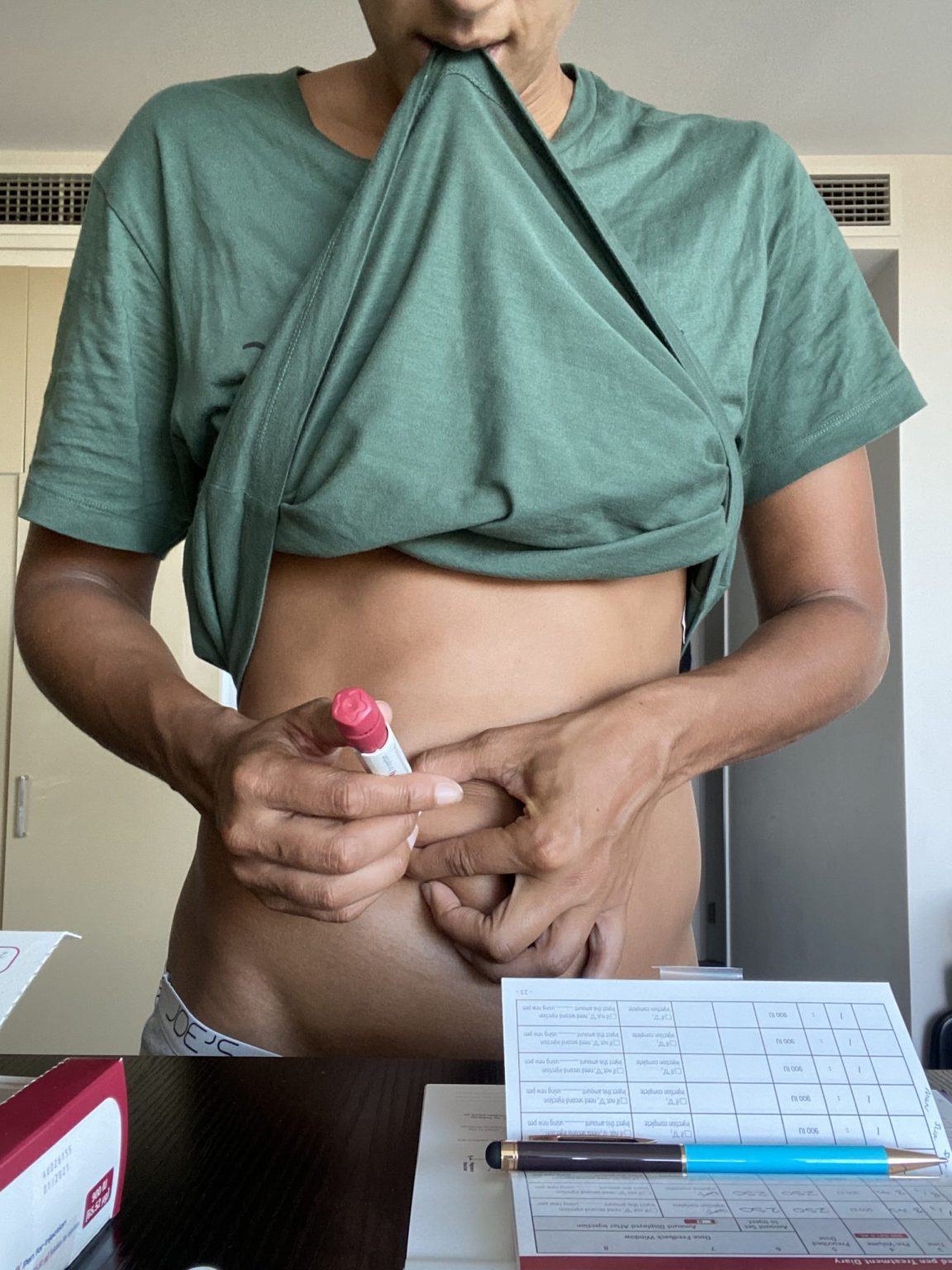

The process involves about two weeks of injections to help grow the eggs before they are collected. Most athletes will continue playing sport during the first week, but in the second the ovaries become swollen, heavy and uncomfortable, and so they generally cease activity. A further week of recovery is needed after the retrieval process.

Athletes must comply with World Anti Doping Agency regulations, and as some fertility medications are on the banned list, careful checks have to be made about which are safe and able to be used.

Geva Mentor CBE had an elite career that spanned 25 years, and she chose to preserve her eggs during her career. Now pregnant with her first child having recently retired from netball, Mentor said, “I’m extremely grateful to have fallen pregnant naturally at 40 but I certainly wouldn’t change the process I went through to freeze my eggs six years ago.

“At the time it gave me peace of mind and the invaluable reassurance of becoming a mother when the time was right. Personally, it was a worthy investment, one I would encourage to anyone who enquires.

“If I’d more information available to me during my sporting career I would have actually gone through the process in my mid to late twenties, not mid thirties.”

Geva Mentor chose to preserve her eggs while continuing with an elite career that spanned an incredible 25 years. Image Danny Dalton

—

Nat Medhurst – An elite athlete’s story about her fertility

“Fertility needs to be an ongoing conversation, not a taboo subject.”

Nat Medhurst (now Butler) and her husband Sam have two happy, healthy children. However, Medhurst knows just how fortunate they are, after experiencing a range of menstrual and fertility issues during her 17 year elite netball career, and several miscarriages since then.

Towards the end of her career, Medhurst and her partner hoped to start a family. She needed medical intervention to fall pregnant and looking back, Medhurst believes many factors contributed to her challenges, and just wishes that she’d been better educated about her body in the earlier stages of her career.

Firstly, in an era where she was skin fold tested every two to three weeks, there was pressure on Medhurst to be lean. She believes she experienced Relative Energy Deficiency syndrome, something which was poorly understood 20 years ago and which most likely contributed to her fertility issues.

“We were always chasing a number, without education attached to it from an actual overall health perspective and what the implications were of having low skin folds.”

The combination of REDs and regular skin fold measurements impacted Medhurst’s mental health, and she subsequently struggled with body dysmorphic disorder.

Another contributor was oral contraception, used to manage her menstrual cycle for competition and training. After years of use, Medhurst stopped taking it, failed to fall pregnant and knew that at the age of 36 time was against her.

She said, “Sam and I decided to see a specialist.

“I had some blood tests, and when the results came back, they told me that I wasn’t ovulating and probably hadn’t been for a very, very long time.

“The contraception had just masked the fact that I was having issues.

“I remember carrying a lot of guilt and self-blame about that. Like I’d done something wrong, or could have done things differently.”

Medhurst was used to training and competing to the highest of standards and holding her body accountable for performance. Being unable to manage her own fertility was brutal.

“To think I’d failed in that department, after a career of controlling everything I could about my body, was really hard.

Told by the specialist that putting on weight could help resolve some of her issues was perhaps correct, but showed little understanding of athletes or her body dysmorphia, adding to Medhurst’s turmoil.

“My obstetrician said to the specialist, ‘Well, I can’t see that happening. She’s an elite athlete so to tell her to stop exercising or stack on the weight is doomed from the start.”

Pregnancy didn’t come easily to Nat Medhurst and her partner Sam Butler, and she believes her journey could have been different with earlier education and testing. Image courtesy of Nat Medhurst

The next step for Medhurst was to have some investigative surgery, during which time a blocked fallopian tube was “cleaned up.” Contracted to Collingwood at the time, just six days later she was playing in a preseason tournament. “I probably shouldn’t have played so soon afterwards, but I felt so guilty that I was looking after my health rather than focusing on netball.”

Putting together the next stages of her treatment plan was complicated by World Anti Doping Agency (WADA) policy, which prohibits a range of fertility drugs that could help ovulation but may also lead to altered levels of testosterone. Having seen Jamaican netballer Simone Forbes’ career ended prematurely by a doping ban in similar circumstances, Medhurst wasn’t taking any chances.

She started on Gonal-F injections, which were accepted by WADA although oddly the more manageable tablet version was not. A naturally occurring hormone that stimulates follicles to develop and mature, Medhurst became a daily pincushion in a process similar to IVF.

While Sam was incredibly supportive and used to help with the needles, there were plenty of times when Medhurst was on the road. “I was travelling with Collingwood for netball games, with my little syringe pack to give myself daily injections. I was trying to do it secretly on tour, book appointments, see the specialists and get my ultrasounds done.

“It was such a minefield to navigate, a very isolating experience and something I felt I had zero control over.”

Medhurst needed highly invasive and weekly internal ultrasounds to check the size of her developing follicles and make sure that her ovaries weren’t being overstimulated. She eventually ovulated, after which time the couple’s sex life was mapped out for the best chances of conception.

Unfortunately for the duo the first round didn’t work, so they went through the process again, successfully this time.

“On the second cycle, my body felt so different after the trigger shot. I was exhausted – having dinner at 4.30 pm and going straight to bed, and that was fairly shortly after a three hour nap. I had sore boobs, I was really hot, and that’s pretty rare because I have Reynaud’s disease.”

The first three and a half months of Medhurst’s pregnancy were tough. Exhausted, nauseous and vomiting all day, she was trying to keep the symptoms under control while going through the rigours of pre-season training. Eventually she sat down with coach Rob Wright for a chat, and then took maternity leave.

For any elite athlete who is pregnant, maternity leave is necessarily longer than usual due to the rigours of playing and training while either pre or postpartum. Medhurst really struggled with that.

“I’d always been part of a team: you train, you play, you work towards something. So I suddenly felt obsolete. I was in the team, but not in the team, I was a player, but not a player. I didn’t know where to go or who to talk to. That’s the reality of being part of a sporting environment.”

Medhurst went on to have two live births and several miscarriages after her elite playing career was over. Having taken months to recover from her losses, she doesn’t know how she would have coped if she was still competing.

“I remember wondering what it would have been like if I’d been in a netball environment and trying to navigate them.

“Miscarriages are very common in the early days and because it’s ‘hidden’ people might not know what you’ve been going through. And you’ve still got to rock up to training without space to grieve or process it or deal with the physical, hormonal or emotional changes that happen in such a short amount of time. Others have to be made public like Jhaniele Fowler-Nembhard’s, and I can’t imagine the depths of loss she went through.

“Not all athletes are lucky enough to be in an environment where they could have a good conversation about it, and that would just be a nightmare.

“Miscarriage is something that we also don’t talk about enough as athletes either.”

Having wished she could turn back the clock on some of her own experiences, Medhurst is excited to see the new fertility policy in place. She said, “We expect everything’s just going to to work out and that’s certainly not always the case.

“Players need information so they can make decisions, and have some more control around their bodies and their health as females.”

For more on the fertility journeys of elite netballers Nat Medhurst, Geva Mentor and Sonia Mkoloma read here. Chelsea Pitman’s experiences of fertility and miscarriage are here.

With sincere thanks to Kathryn Harby Williams AM, Dr Kath Whitton, Tara Hinchliffe, Nat Medhurst and Geva Mentor CBE.